Introduction: Darius’ Titles and the Extent of his Empire

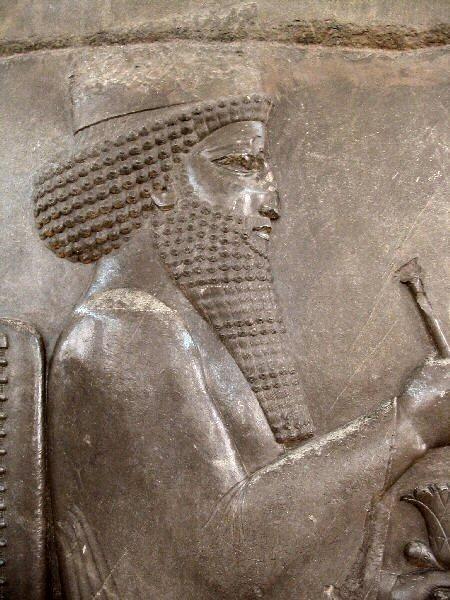

Darius I The Great (Darius, relief from the Central Relief of the Northern Stairs of the Apadana, Persepolis) |

|

|

| |

|

[i.1] I am Darius, the great king, king of kings, the king of Persia, the king of countries, the son of Hystaspes, the grandson of Arsames, the Achaemenid.

[i.2] King Darius says: My father is Hystaspes; the father of Hystaspes was Arsames; the father of Arsames was Ariaramnes; the father of Ariaramnes was Teispes; the father of Teispes was Achaemenes.

[i.3] King Darius says: That is why we are called Achaemenids; from antiquity we have been noble; from antiquity has our dynasty been royal.

[i.4] King Darius says: Eight of my dynasty were kings before me; I am the ninth. Nine in succession we have been kings.

[i.5] King Darius says: By the grace of Ahuramazda am I king; Ahuramazda has granted me the kingdom.

[i.6] King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject unto me, and by the grace of Ahuramazda I became king of them: Persia, Elam, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, the countries by the Sea, Lydia, the Greeks, Media, Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdia, Gandara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia and Maka; twenty-three lands in all.

[i.7] King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject to me; by the grace of Ahuramazda they became subject to me; they brought tribute unto me. Whatsoever commands have been laid on them by me, by night or by day, have been performed by them.

[i.8] King Darius says: Within these lands, whosoever was a friend, him have I surely protected; whosoever was hostile, him have I utterly destroyed. By the grace of Ahuramazda these lands have conformed to my decrees; as it was commanded unto them by me, so was it done.

[i.9] King Darius says: Ahuramazda has granted unto me this empire. Ahuramazda brought me help, until I gained this empire; by the grace of Ahuramazda do I hold this empire.

Murder of Smerdis and Coup of Gaumâta the Magian

[i.10] King Darius says: The following is what was done by me after I became king. A son of Cyrus, named Cambyses, one of our dynasty, was king here before me. That Cambyses had a brother, Smerdis by name, of the same mother and the same father as Cambyses. Afterwards, Cambyses slew this Smerdis. When Cambyses slew Smerdis, it was not known unto the people that Smerdis was slain. Thereupon Cambyses went to Egypt. When Cambyses had departed into Egypt, the people became hostile, and the lie multiplied in the land, even in Persia and Media, and in the other provinces.

[i.11] King Darius says: Afterwards, there was a certain man, a Magian, Gaumâta by name, who raised a rebellion in Paišiyâuvâdâ, in a mountain called Arakadriš. On the fourteenth day of the month Viyaxana did he rebel. He lied to the people, saying: "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus, the brother of Cambyses." Then were all the people in revolt, and from Cambyses they went over unto him, both Persia and Media, and the other provinces. He seized the kingdom; on the ninth day of the month Garmapada he seized the kingdom. Afterwards, Cambyses died of natural causes.

[i.12] King Darius says: The kingdom of which Gaumâta, the Magian, dispossessed Cambyses, had always belonged to our dynasty. After that Gaumâta, the Magian, had dispossessed Cambyses of Persia and Media, and of the other provinces, he did according to his will. He became king.

Darius kills Gaumâta and Restores the Kingdom

[i.13] King Darius says: There was no man, either Persian or Mede or of our own dynasty, who took the kingdom from Gaumâta, the Magian. The people feared him exceedingly, for he slew many who had known the real Smerdis. For this reason did he slay them, "that they may not know that I am not Smerdis, the son of Cyrus." There was none who dared to act against Gaumâta, the Magian, until I came. Then I prayed to Ahuramazda; Ahuramazda brought me help. On the tenth day of the month Bâgayâdiš I, with a few men, slew that Gaumâta, the Magian, and the chief men who were his followers. At the stronghold called Sikayauvatiš, in the district called Nisaia in Media, I slew him; I dispossessed him of the kingdom. By the grace of Ahuramazda I became king; Ahuramazda granted me the kingdom.

[i.14] King Darius says: The kingdom that had been wrested from our line I brought back and I reestablished it on its foundation. The temples which Gaumâta, the Magian, had destroyed, I restored to the people, and the pasture lands, and the herds and the dwelling places, and the houses which Gaumâta, the Magian, had taken away. I settled the people in their place, the people of Persia, and Media, and the other provinces. I restored that which had been taken away, as is was in the days of old. This did I by the grace of Ahuramazda, I labored until I had established our dynasty in its place, as in the days of old; I labored, by the grace of Ahuramazda, so that Gaumâta, the Magian, did not dispossess our house.

[i.15] King Darius says: This was what I did after I became king.

Rebellions of ššina of Elam and Nidintu-Bêl of Babylon

[i.16] King Darius says: After I had slain Gaumâta, the Magian, a certain man named ššina, the son of Upadarma, raised a rebellion in Elam, and he spoke thus unto the people of Elam: "I am king in Elam." Thereupon the people of Elam became rebellious, and they went over unto that ššina: he became king in Elam. And a certain Babylonian named Nidintu-Bêl, the son of Kîn-Zêr, raised a rebellion in Babylon: he lied to the people, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus." Then did all the province of Babylonia go over to Nidintu-Bêl, and Babylonia rose in rebellion. He seized on the kingdom of Babylonia.

[i.17] King Darius says: Then I sent [an envoy?] to Elam. That ššina was brought unto me in fetters, and I killed him.

[i.18] King Darius says: Then I marched marched against that Nidintu-Bêl, who called himself Nebuchadnezzar. The army of Nidintu-Bêl held the Tigris; there it took its stand, and on account of the waters [the river] was unfordable. Thereupon I supported my army on [inflated] skins, others I made dromedary-borne, for the rest I brought horses. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda we crossed the Tigris. Then did I utterly overthrow that host of Nidintu-Bêl. On the twenty-sixth day of the month Âçiyâdiya we joined battle.

[i.19] King Darius says: After that I marched against Babylon. But before I reached Babylon, that Nidintu-Bêl, who called himself Nebuchadnezzar, came with a host and offered battle at a city called Zâzâna, on the Euphrates. Then we joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did I utterly overthrow the host of Nidintu-Bêl. The enemy fled into the water; the water carried them away. On the second day of the month Anâmaka we joined battle.

[ii.20] King Darius says: Then did Nidintu-Bêl flee with a few horsemen into Babylon. Thereupon I marched to Babylon. By the grace of Ahuramazda I took Babylon, and captured Nidintu-Bêl. Then I slew that Nidintu-Bêl in Babylon.

[ii.21] King Darius says: While I was in Babylon, these provinces revolted from me: Persia, Elam, Media, Assyria, Egypt, Parthia, Margiana, Sattagydia, and Scythia.

Revolt of Martiya of Elam

[i.22] King Darius says: A certain man named Martiya, the son of Zinzakriš, dwelt in a city in Persia called Kuganakâ. This man revolted in Elam, and he said to the people: "I am Ummaniš, king in Elam."

[ii.23] King Darius says: At that time, I was friendly with Elam. Then there were Elamites afraid of me, and that Martiya, who was their leader, they seized and slew.

Revolt of Phraortes of Media

[ii.24] King Darius says: A certain Mede named Phraortes revolted in Media, and he said to the people: "I am Khshathrita, of the family of Cyaxares." Then did the Medes who were in the palace revolt from me and go over to Phraortes. He became king in Media.

[ii.25] King Darius says: The Persian and Median army, which was with me, was small. Yet I sent forth an[other] army. A Persian named Hydarnes, my servant, I made their leader, and I said unto him: "Go, smite that Median host which does not acknowledge me." Then Hydarnes marched forth with the army. When he had come to Media, at a city in Media called Maruš, he gave battle to the Medes. He who was chief among the Medes was not there at that time. Ahuramazda brought me help: by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly defeated that rebel host. On the twenty-seventh day of the month Anâmaka the battle was fought by them. Then did my army await me in a district in Media called Kampanda, until I came into Media.

Revolt of the Armenians

[ii.26] King Darius says: An Armenian named Dâdarši , my servant, I sent into Armenia, and I said unto him: "Go, smite that host which is in revolt and does not acknowledge me." Then Dâdarši went forth. When he came into Armenia, the rebels assembled and advanced against Dâdarši to give him battle. At a place in Armenia called Zuzza they fought the battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. On the eighth day of the month Thûravâhara [20 May 521.}}the battle was fought by them.

[ii.27] King Darius says: The rebels assembled for the second time, and they advanced against Dâdarši to give him battle. At a stronghold in Armenia called Tigra they joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. On the eighteenth day of the month Thûravâhara the battle was fought by them.

[ii.28] King Darius says: The rebels assembled for the third time and advanced against Dâdarši to give him battle. At a stronghold in Armenia called Uyamâ they joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. On the ninth day of the month Thâigaciš the battle was fought by them. Then Dâdarši waited for me in Armenia, until I came into Armenia.

[ii.29] King Darius says: A Persian named Vaumisa, my servant, I sent into Armenia, and I said unto him: "Go, smite that host which is in revolt, and does not acknowledge me." Then Vaumisa went forth. When he had come to Armenia, the rebels assembled and advanced against Vaumisa to give him battle. At a place in Assyria called Izala they joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. On the fifteenth day of the month Anâmaka the battle was fought by them.

[ii.30] King Darius says: The rebels assembled a second time and advanced against Vaumisa to give him battle. At a place in Armenia called Autiyâra they joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. At the end of the month Thûravâhara the battle was fought by them. Then Vaumisa waited for me in Armenia, until I came into Armenia.

End of the Revolt of the Medes

[ii.31] King Darius says: Then I went forth from Babylon and came into Media. When I had come to Media, that Phraortes, who called himself king in Media, came against me unto a city in Media called Kunduruš to offer battle. Then we joined battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda did my army utterly overthrow that rebel host. On the twenty-fifth day of the month Adukanaiša we fought the battle.

[ii.32] King Darius says: Thereupon that Phraortes fled thence with a few horseman to a district in Media called Rhagae. Then I sent an army in pursuit. Phraortes was taken and brought unto me. I cut off his nose, his ears, and his tongue, and I put out one eye, and he was kept in fetters at my palace entrance, and all the people beheld him. Then did I crucify him in Ecbatana; and the men who were his foremost followers, those at Ecbatana within the fortress, I flayed and hung out their hides, stuffed with straw.

[ii.33] King Darius says: A man named Tritantaechmes, a Sagartian, revolted from me, saying to his people: "I am king in Sagartia, of the family of Cyaxares." Then I sent forth a Persian and a Median army. A Mede named Takhmaspâda, my servant, I made their leader, and I said unto him: "Go, smite that host which is in revolt, and does not acknowledge me." Thereupon Takhmaspâda went forth with the army, and he fought a battle with Tritantaechmes. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly defeated that rebel host, and they seized Tritantaechmes and brought him unto me. Afterwards I cut off both his nose and ears, and put out one eye, he was kept bound at my palace entrance, all the people saw him. Afterwards I crucified him in Arbela.

[ii.34] King Darius says: This is what was done by me in Media.

Revolt of the Parthians

[ii.35] King Darius says: The Parthians and Hyrcanians revolted from me, and they declared themselves on the side of Phraortes. My father Hystaspes was in Parthia; and the people forsook him; they became rebellious. Then Hystaspes marched forth with the troops which had remained faithful. At a city in Parthia called Višpauzâtiš he fought a battle with the Parthians. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly defeated that rebel host. On the second day of the month Viyaxana the battle was fought by them.

[ii.36] King Darius says: Then did I send a Persian army unto Hystaspes from Rhagae. When that army reached Hystaspes, he marched forth with the host. At a city in Parthia called Patigrabanâ he gave battle to the rebels. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda Hystaspes utterly defeated that rebel host. On the first day of the month Garmapada the battle was fought by them.

[ii.37] King Darius says: Then was the province mine. This is what done by me in Parthia.

Revolt of Frâda of Margiana

[iii.38] King Darius says: The province called Margiana revolted against me. A certain Margian named Frâda they made their leader. Then sent I against him a Persian named Dâdarši, my servant, who was satrap of Bactria, and I said unto him: "Go, smite that host which does not acknowledge me." Then Dâdarši went forth with the army, and gave battle to the Margians. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly overthrew that rebel host. Of the twenty-third day of the month Âçiyâdiya was the battle fought by them.

[iii.39] King Darius says: Then was the province mine. This is what was done by me in Bactria.

Revolt of Vahyazdâta of Persia

[iii.40] King Darius says: A certain man named Vahyazdâta dwelt in a city called Târavâ in a district in Persia called Vautiyâ. This man rebelled for the second time in Persia, and thus he spoke unto the people: "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus." Then the Persian people who were in the palace fell away from allegiance. They revolted from me and went over to that Vahyazdâta. He became king in Persia.

[iii.41] King Darius says: Then did I send out the Persian and the Median army which was with me. A Persian named Artavardiya, my servant, I made their leader. The rest of the Persian army came unto me in Media. Then went Artavardiya with the army unto Persia. When he came to Persia, at a city in Persia called Rakhâ, that Vahyazdâta, who called himself Smerdis, advanced with the army against Artavardiya to give him battle. They then fought the battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my host utterly overthrew the army of Vahyazdâta. On the twelfth day of the month Thûravâhara was the battle fought by them.

[iii.42] King Darius says: Then that Vahyazdâta fled thence with a few horsemen unto Pishiyâuvâda. From that place he went forth with an army a second time against Artavardiya to give him battle. At a mountain called Parga they fought the battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my host utterly overthrew the army of Vahyazdâta. On the fifth day of the month Garmapada was the battle fought by them. And they seized that Vahyazdâta, and the men who were his chief followers were also seized.

[iii.43] King Darius says: Then did I crucify that Vahyazdâta and the men who were his chief followers in a city in Persia called Uvâdaicaya.

[iii.44] King Darius says: This is what was done by me in Persia.

Fighting in Arachosia

[iii.45] King Darius says: That Vahyazdâta, who called himself Smerdis, sent men to Arachosia against a Persian named Vivâna, my servant, the satrap of Arachosia. He appointed a certain man to be their leader, and thus he spoke to him, saying: "Go smite Vivâna and the host which acknowledges king Darius!" Then that army that Vahyazdâta had sent marched against Vivâna to give him battle. At a fortress called Kapiša-kaniš they fought the battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly overthrew that rebel host. On the thirteenth day of the month Anâmaka was the battle fought by them.

[iii.46] King Darius says: The rebels assembled a second time and went out against Vivâna to give him battle. At a place called Gandutava they fought a battle. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda my army utterly overthrew that rebel host. On the seventh day of the month Viyaxana the battle was fought by them.

[iii.47] King Darius says: The man who was commander of that army that Vahyazdâta had sent forth against Vivâna fled thence with a few horsemen. They went to a fortress in Arachosia called Aršâdâ. Then Vivâna with the army marched after them on foot. There he seized him, and he slew the men who were his chief followers.

[iii.48] King Darius says: Then was the province mine. This is what was done by me in Arachosia.

Second Babylonian revolt

[iii.49] King Darius says: While I was in Persia and in Media, the Babylonians revolted from me a second time. A certain man named Arakha, an Armenian, son of Haldita, rebelled in Babylon. At a place called Dubâla, he lied unto the people, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus." Then did the Babylonian people revolt from me and they went over to that Arakha. He seized Babylon, he became king in Babylon.

[iii.50] King Darius says: Then did I send an army unto Babylon. A Persian named Intaphrenes, my servant, I appointed as their leader, and thus I spoke unto them: "Go, smite that Babylonian host which does not acknowledge me." Then Intaphrenes marched with the army unto Babylon. Ahuramazda brought me help; by the grace of Ahuramazda Intaphrenes overthrew the Babylonians and brought over the people unto me. On the twenty-second day of the month Markâsanaš they seized that Arakha who called himself Nebuchadnezzar, and the men who were his chief followers. Then I made a decree, saying: "Let that Arakha and the men who were his chief followers be crucified in Babylon!"

[iv.51] King Darius says: This is what was done by me in Babylon.

Summary and Conclusion

[iv.52] King Darius says: This is what I have done. By the grace of Ahuramazda have I always acted. After I became king, I fought nineteen battles in a single year and by the grace of Ahuramazda I overthrew nine kings and I made them captive.

- One was named Gaumâta, the Magian; he lied, saying "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus." He made Persia to revolt.

- Another was named ššina, the Elamite; he lied, saying: "I am king the king of Elam." He made Elam to revolt.

- Another was named Nidintu-Bêl, the Babylonian; he lied, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus." He made Babylon to revolt.

- Another was named Martiya, the Persian; he lied, saying: "I am Ummanniš, the king of Elam." He made Elam to revolt.

- Another was Phraortes, the Mede; he lied, saying: "I am Khshathrita, of the dynasty of Cyaxares." He made Media to revolt.

- Another was Tritantaechmes, the Sagartian; he lied, saying: "I am king in Sagartia, of the dynasty of Cyaxares." He made Sagartia to revolt.

- Another was named Frâda, of Margiana; he lied, saying: "I am king of Margiana." He made Margiana to revolt.

- Another was Vahyazdâta, a Persian; he lied, saying: "I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus." He made Persia to revolt.

- Another was Arakha, an Armenian; he lied, saying: "I am Nebuchadnezzar, the son of Nabonidus." He made Babylon to revolt.

[iv.53] King Darius says: These nine king did I capture in these wars.

[iv.54] King Darius says: As to these provinces which revolted, lies made them revolt, so that they deceived the people. Then Ahuramazda delivered them into my hand; and I did unto them according to my will.

[iv.55] King Darius says: You who shall be king hereafter, protect yourself vigorously from lies; punish the liars well, if thus you shall think, "May my country be secure!"

Affirmation of the Truth of the Record

[iv.56] King Darius says: This is what I have done, by the grace of Ahuramazda have I always acted. Whosoever shall read this inscription hereafter, let that which I have done be believed. You must not hold it to be lies.

[iv.57] King Darius says: I call Ahuramazda to witness that is true and not lies; all of it have I done in a single year.

[iv.58] King Darius says: By the grace of Ahuramazda I did much more, which is not graven in this inscription. On this account it has not been inscribed lest he who shall read this inscription hereafter should then hold that which has been done by me to be excessive and not believe it and takes it to be lies.

Praise of Ahuramazda

[iv.59] King Darius says: Those who were the former kings, as long as they lived, by them was not done thus as by the favor of Ahuramazda was done by me in one and the same year.

[iv.60] King Darius says: Now let what has been done by me convince you. For the sake of the people, do not conceal it. If you do not conceal this edict but if you publish it to the world, then may Ahuramazda be your friend, may your family be numerous, and may you live long.

[iv.61] King Darius says: If you conceal this edict and do not publish it to the world, may Ahuramazda slay you and may your house cease.

[iv.62] King Darius says: This is what I have done in one single year; by the grace of Ahuramazda have I always acted. Ahuramazda brought me help, and the other gods, all that there are.

The Importance of Righteousness

[iv.63] King Darius says: On this account Ahuramazda brought me help, and all the other gods, all that there are, because I was not wicked, nor was I a liar, nor was I a despot, neither I nor any of my family. I have ruled according to righteousness. Neither to the weak nor to the powerful did I do wrong. Whosoever helped my house, him I favored; he who was hostile, him I destroyed.

[iv.64] King Darius says: You who may be king hereafter, whosoever shall be a liar or a rebel, or shall not be friendly, punish him!

Blessings and Curses

[iv.65] King Darius says: You who shall hereafter see this tablet, which I have written, or these sculptures, do not destroy them, but preserve them so long as you live!

[iv.66] King Darius says: If you shall behold this inscription or these sculptures, and shall not destroy them, but shall preserve them as long as your line endures, then may Ahuramazda be your friend, and may your family be numerous. Live long, and may Ahuramazda make fortunate whatsoever you do.

[iv.67] King Darius says: If you shall behold this inscription or these sculptures, and shall destroy them and shall not preserve them so long as your line endures, may Ahuramazda slay you, may your family come to nought, and may Ahuramazda destroy whatever you do!

Names of Darius’ supporters

[iv.68] King Darius says: These are the men who were with me when I slew Gaumâta the Magian, who was called Smerdis; then these men helped me as my followers:

- Intaphrenes, son of Vayâspâra, a Persian;

- Otanes, son of Thukhra, a Persian;

- Gobryas, son of Mardonius, a Persian;

- Hydarnes, son of Bagâbigna, a Persian;

- Megabyzus, son of Dâtuvahya, a Persian;

- Ardumaniš, son of Vakauka, a Persian.

[iv.69] King Darius says: You who may be king hereafter, protect the family of these men.

[iv.70] King Darius says: By the grace of Ahuramazda this is the inscription which I have made. Besides, it was in Aryan script, and it was composed on clay tablets and on parchment. Besides, a sculptured figure of myself I made. Besides, I made my lineage. And it was inscribed and was read off before me. Afterwards this inscription I sent off everywhere among the provinces. The people unitedly worked upon it.

New Rebellion on Elam

[v.71] King Darius says: The following is what I did in the second and third year of my rule. The province called Elam revolted from me. An Elamite named Atamaita they made their leader. Then I sent an army unto Elam. A Persian named Gobryas, my servant, I made their leader. Then Gobryas set forth with the army; he delivered battle against the Elamites. Then Gobryas destroyed many of the host and that Atamaita, their leader, he captured, and he brought him unto me, and I killed him. Then the province became mine.

[v.72] King Darius says: Those Elamites were faithless and Ahuramazda was not worshipped by them. I worshipped Ahuramazda; by the grace of Ahuramazda I did unto them according to my will.

[v.73] King Darius says: Whoso shall worship Ahuramazda, divine blessing will be upon him, both while living and when dead.

War Against the Scythians

[v.74] King Darius says: Afterwards with an army I went off to Scythia, after the Scythians who wear the pointed cap. These Scythians went from me. When I arrived at the river, I crossed beyond it then with all my army. Afterwards, I smote the Scythians exceedingly; [one of their leaders] I took captive; he was led bound to me, and I killed him. [Another] chief of them, by name Skunkha, they seized and led to me. Then I made another their chief, as was my desire. Then the province became mine.

[v.75] King Darius says: Those Scythians were faithless and Ahuramazda was not worshipped by them. I worshipped Ahuramazda; by the grace of Ahuramazda I did unto them according to my will.

[v.76] King Darius says: [Whoso shall worship] Ahuramazda, [divine blessing will be upon him, both while] living and [when dead.]

|